I once met the actor and director Robert Redford.

I was a young reporter in Denver back then, covering the state legislature and Colorado governor’s office for the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News. I’d received a tip that Redford was set to have breakfast the following morning at the Governor’s Mansion with then-Gov. Dick Lamm. I showed up early and met Redford at the door. After introducing myself, I asked why the two men were meeting? He brushed me off—politely—and suggested we could talk at a function later that day where he was scheduled to speak publicly. When I approached him there, he brushed me off once more, again politely, with that characteristic mix of charm and aloofness that seemed effortless for him.

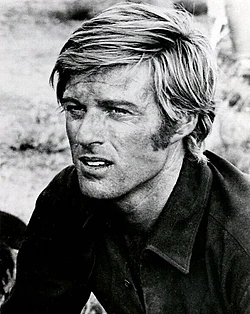

I don’t remember what his purpose in Denver was that day. I do, however, vividly remember how he struck me in person. He was shorter and even more handsome than on screen. He wore a wool sportscoat, trousers, cowboy boots, a western-style shirt, a beaded Navajo belt, and aviator-style glasses with a tiny chip missing from the corner of one lens. It was such a small, humanizing detail for someone who seemed otherwise carved out of cinematic perfection.

What has stayed with me more than that memory, though—call it confluence or simple coincidence–is how much of my own life seemed to weirdly intersect with some of his films.

In my late teens, for example, I got big into winter mountain camping, influenced largely by Redford’s portrayal of the rugged frontier loner in Jeremiah Johnson. That illusion ended abruptly after I fell through the ice of a freezing mountain stream above Colorado’s Guanella Pass, where a blizzard set in and a buddy and I were snowbound for a couple of days, unable to hike through tall drifts back to his truck. Shivering in my sleeping bag, wet, cold, and hungry, with little more to eat than freeze-dried oatmeal, I realized quickly that I was not, and never would be, Jeremiah Johnson.

I chose to become a journalist in large measure after watching All the President’s Men. Seeing Redford as Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, relentless in pursuit of the truth with his partner, Carl Bernstein, made the job look not only meaningful but thrilling.

While still in college, I watched Three Days of the Condor, in which Redford plays an unwitting intelligence analyst caught in a web of espionage. Not long after graduating, the CIA recruited me and flew me back to Washington for a series of job interviews. The position they were considering me for was not one that I was particularly keen on, and the job was never offered. Many years later, after leaving daily journalism, I would wind up working under contract for both the CIA and the DIA. My work was hardly the stuff of Hollywood spy flicks, but walking around inside the intelligence community with a top-secret clearance did make me feel, perhaps if only a little, like I was inhabiting a Redford role.

Redford played a barnstorming, devil-may-care pilot in The Great Waldo Pepper, flying around in an open-cockpit biplane. I, too, became a pilot, though a much more cautious one.

There were other intersections, if you could call them that.

I once was invited to audition for a non-speaking part in The Electric Horseman, a modern Western starring Redford and Jane Fonda. The audition required that I show up at a modeling agency one hot summer day, wearing a flannel shirt (why a flannel shirt, I have no idea). In any case, as I drove into the parking lot, I observed several studly-looking young men milling about outside. They all looked like professional actors, and they were all wearing flannel shirts. I decided in that moment that I was not an actor and had no desire to be one. I drove out of that parking lot and never looked back.

Years later, as a working screenwriter, I pitched a couple of movie ideas to executives at Wildwood Productions, Redford’s film development company. Alas, my pitches went nowhere. What was no less disappointing was that I never saw Redford in his office; I still wanted to ask him about that mysterious breakfast with Gov. Lamm.

This morning, news came that Robert Redford had passed away at 89. It’s hard to reconcile that he was as old as he was. He seemed timeless, the embodiment of vigor and youth. To me, he was more than a movie star. He was a mirror, however distant, reflecting back the ambitions, adventures, and even missteps of my own life. In a way, I’d like to believe that many of his films became personal guideposts, nudging me toward choices that shaped who I ultimately became. They provided me with more than entertainment. They gave me the sense that, even for a poor kid from Colorado, it was possible to lead a life with curiosity and perhaps even a touch of daring.

What also made Redford noteworthy was that he never limited himself to the bright lights of Hollywood. He poured his influence, money, and energy into causes that he believed mattered—protecting the environment, preserving open spaces, elevating independent voices in film, and fostering civil discourse. He founded the Sundance Institute not only to showcase fresh talent, but to create a community where stories outside the mainstream could find life. His activism was steady and genuine, proving that celebrity can serve more than self-promotion; it can offer stewardship.

Robert Redford reminded us that the world is larger than our fears, richer than our routines, and worth chasing with everything we’ve got. That is how I’ll remember him: not just as an actor, director, or benefactor, but as a man whose stories helped me find my own.