Why Pilots Make Good Detectives: The Overlap Between Flying and Solving Crimes

If you’ve followed Cordell Logan across the pages of my mystery novels, you’ve probably noticed something early on: Logan can’t turn off his pilot brain. Even when he’s nowhere near the cockpit of the Ruptured Duck—his aging but stubbornly reliable airplane—he’s mentally scanning, evaluating, cross-checking, and trying to stay three steps ahead of whatever might go wrong next. It’s a habit that saves his life outright in Flat Spin, nearly costs him in Deep Fury, and quietly governs the way he moves through danger in Voodoo Ridge, Hot Start, The Kill Circle, and The Three-Nine Line. Readers sometimes ask why Logan is a flight instructor rather than a conventional detective. Why not make him a an ex-cop, or former government special operator? The answer is that I wanted him to be unique, and being a pilot is at at his core. Flying shapes how he thinks, how he handles pressure, and how he interprets incomplete information. It turns out pilots make surprisingly good detectives. The cognitive overlap is real. Situational Awareness: Flying the Situation, Not Just the Airplane Every pilot learns early that your first priority is that when everything is falling apart, first things first: just fly the airplane. But you also fly the situation. Weather, terrain, traffic, systems, fuel, airspace, radio chatter, and your own mental state all compete for attention. Miss one variable and the whole picture can unravel. Logan lives inside that mindset. He enters rooms the way a pilot enters unfamiliar airspace—quietly, alertly, taking in what doesn’t announce itself. In Voodoo Ridge, this is how he realizes a seemingly cooperative character is anything but: not because of what’s said, but because the surrounding details don’t align. It’s the narrative equivalent of flying into air that feels wrong before the instruments confirm it. That instinct mirrors real flying. I once descended toward a small mountain airport as visibility steadily degraded, making constant micro-adjustments—airspeed, descent rate, terrain clearance—without panic, just processing. Logan processes the same way. He doesn’t label it situational awareness. He simply knows when something is off. Checklists: Discipline as a Survival Tool One of aviation’s most important inventions wasn’t a faster engine or better avionics. It was the checklist. Pilots use checklists obsessively: before takeoff, in cruise, on approach, during emergencies. They aren’t a crutch; they’re an acknowledgment that human memory degrades under stress. Logan doesn’t carry a literal checklist, but that mentality governs his investigations. In The Kill Circle, when multiple explanations appear equally plausible, he refuses to lunge toward the most dramatic theory. Instead, he works methodically—timelines, motives, opportunity—until one detail refuses to reconcile. That’s the detective version of a warning light on the instrument panel that shouldn’t be on. I’ve been grateful for that discipline myself. Taxiing out not long ago from a high-altitude desert airfield after refueling, a minor anomaly during my engine run-up forced me to stop, recheck, and shut down. Mechanics later confirmed a problem that could have ended badly had I ignored it. Aviation teaches you that small oversights become catastrophic quickly. Logan understands that truth at a cellular level. Risk Assessment: Quiet Paranoia Done Right Good pilots operate with quiet paranoia—not fear, but the assumption that stuff happens and systems fail. So they constantly build margins. They plan exit strategies. They assume today’s calm may not last. Logan carries that mindset everywhere. In The Three-Nine Line, he repeatedly survives situations that look manageable on the surface because he never trusts surface calm. He anticipates escalation. He assumes someone is lying. He prepares for the moment when things turn sideways—because flying has taught him they often do. By the time Logan reaches The Impossible Turn—the eighth novel in the series, debuting in spring 2026—that instinct is no longer just a habit; it’s a necessity. The margins are thinner. The consequences of misjudgment are steeper. The question he has always asked—What am I missing?—becomes less abstract and more existential. It’s no longer about avoiding trouble. It’s about choosing which risks can be survived at all. Pattern Recognition: The Skill You Can’t Fake Flying is, at its core, pattern recognition. Engines have normal sounds. Airplanes feel a certain way at rotation. Weather behaves in recognizable moods. After enough time aloft, you sense trouble before you can articulate it. Logan’s investigations run on the same principle. In Deep Fury, he notices behavioral inconsistencies—hesitations, over-rehearsed reactions, details offered too quickly—that mirror the way a pilot notices an engine running just slightly rough. His gut isn’t mystical. It’s trained. By the time of The Impossible Turn, those patterns arrive faster and collide harder. There’s less time to analyze and fewer clean readouts. Logan is forced to rely not just on pattern recognition, but on judgment honed over years of near-misses—both in the air and on the ground. The Mindset That Keeps Him Alive Cordell Logan isn’t an effective detective because he’s brilliant or fearless. He’s effective because he brings a pilot’s brain into situations where most people bring instinct alone. He’s structured without rigidity, skeptical without cynicism, disciplined without losing adaptability. Those traits define the best pilots I’ve known—and they define the best fictional detectives, too. Which is why Logan, even when firmly on the ground, is never really done flying. The cockpit just follows him wherever he goes. And eventually, it asks him to make a turn he’s spent a lifetime preparing for.

From Newsroom to Cockpit: How Journalism Trained Me to Write Fiction

Long before Cordell Logan ever taxied onto the page in his beat-up Cessna 172, the Ruptured Duck, I spent my days—and too many nights—chasing leads as an investigative reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Back then, my world smelled like newsroom coffee and the faint whiff of panic as another deadline closed in. Today, the aroma tends more toward avgas and the warmth of a sunbaked runway. But the truth is, the journey from newsroom to hangar wasn’t a reinvention. It was an evolution. The skills I sharpened digging for stories are the same ones I lean on every time Logan finds himself in trouble. Which is to say, constantly. I didn’t realize it at the time, but being a journalist—and, later, working in the intelligence community–was the best training ground imaginable for writing aviation-driven crime fiction. The best reporters share one simple trait: they’re nosy. Professionally nosy. Pathologically nosy. Tell us “no comment” and that only makes us dig deeper. Tell us something doesn’t add up and we’ll spend the next month trying to make the math work. That instinct is hardwired into Cordell Logan. He’s a guy who can’t help noticing when details don’t fit—the dent that couldn’t have come from where the witness claims, the alibi that feels too practiced, the muffled tone of a man hiding something behind his eyes. Logan has pilot instincts, sure. But he’s also the inheritor of those newsroom genes—always scanning for things that are out of place. Curiosity might kill cats (apologies for the cliché), but in investigative reporting and mystery writing, it’s the spark that keeps the engine turning. As a reporter, I learned early that the difference between an average news story and a front-page, above-the-fold, award winner lies less in volume than it does in precision and detail. I once spent weeks tracking down a law-enforcement source who could confirm a small but crucial procedural failure inside a high-stakes investigation. It was the kind of detail that would barely earn a sentence in the final article—yet without it, the story lacked credibility. Flying teaches that same lesson, only with higher consequences. Overlook a crucial detail in the cockpit and you aren’t getting a phone call from your editor; you’re getting a visit from the NTSB—assuming you’re still lucky enough to be alive. So in the Logan series, I try to honor both disciplines. Aviation is inherently technical, but thriller fans don’t show up to read a pilot operator’s handbook. They want to feel the stall buffet in their stomachs, not read a dissertation on angle of attack. Journalism trained me to identify the details that matter and ditch the ones that don’t—an underrated skill when your protagonist spends a lot of time dodging bullets and pulling G’s. One of the first things they don’t tell you in journalism school is that the truth rarely arrives in clean, declarative sentences. More often, it’s hiding in the hesitation between two words, the micro-pause before someone answers, the shift in tone when you press just a little harder. As a pilot talking to ATC, you learn the same thing. A controller’s clipped phrasing might mean things are getting busy. A bit of strain in the voice might suggest weather is degrading faster than forecast. You read the tone as much as the words. In my books, Logan listens like that—like a reporter and a pilot rolled into one. His understanding of people comes from years of inherently comprehending what isn’t said. That instinct came straight from my years in the trenches of journalism. If you spend any time in a newsroom or on an airport ramp, you’ll meet more characters than you can ever hope to fit into a book: the crusty line guy who knows every airplane’s quirks; the editor who could dismantle the draft of investigative piece with one raised eyebrow; the retired pilot whose stories always start with “This one time, over Bakersfield…”; the source who insists on meeting only in dimly lit bars. As a reporter for the Times, and for the two daily newspapers in Colorado I worked before moving to California, I met plenty of memorable people—whistleblowers, military guys, cops, grieving families, political operatives, and the occasional individual who probably would’ve preferred I lose their phone number forever. In aviation circles, I’ve met instructors, mechanics, veterans, and fellow pilots who embody the courage, eccentricity, and gallows humor that define GA flying. Those personalities seep into Logan’s world. Not as literal copies, but as raw material. Fiction thrives on authenticity, and nothing is more authentic than the unpredictable human beings you meet when you spend your life asking uncomfortable questions or flying machines that don’t always behave. Both journalism and flying have a way of humbling you. In the air, mistakes carry consequences. The same is true in reporting—errors, even small ones, can damage reputations, derail investigations, or betray the trust of sources who risked everything to speak. That’s why Logan’s world is built on accountability. When he screws up, people get hurt. That’s not melodrama; that’s reality, filtered through the lens of a murder mystery. In reporting, the thrill is in the chase—the moment you uncover the missing piece. In flying, it’s lifting off into a sky that always feels bigger and more beautiful than you remembered. In writing, it’s when a scene snaps into place and suddenly the story has lift. Looking back, the path from newsroom to cockpit to fiction wasn’t odd at all. It was inevitable. They’re all pursuits of precision, curiosity, and truth—three things Cordell Logan himself can’t resist. And frankly, neither can I.

Cirrus vs. The Duck

Readers often assume that because Cordell Logan flies a creaky, seen-better-decades Cessna 172—the Ruptured Duck—I must fly something equally geriatric, dented, and emotionally complicated. This could not be further from the truth. In reality, I fly a first-generation Cirrus, a sleek, exceedingly comfortable machine with glass avionics, a side yoke, and a temperament that suggests it was designed by psychologists who wanted flying to feel like therapy. Logan’s airplane may not be like that, but it is exactly like the airplanes I spent many years flying before making the leap to a Cirrus. Before upgrading, I logged several hundred hours in a Cessna 172 upon which the Duck is modeled. The kind with sun-cracked plastic, an earthtone color scheme popular during the administration, and avionics that proudly proclaimed themselves “state of the art” in 1973. For more than a decade after that, I flew a Piper Cherokee 180 built in 1965. It was a wonderfully simple, sturdy, no-nonsense, stubbornly faithful machine that I bought believing it would meet my requirement of being able to carry my wife, two kids, and full fuel. Turns out, everybody was invariably too busy with their own lives and interests to come flying very often with me. Indeed, these days, I fly solo far more often than I do with passengers. So I know Duck-like airplanes intimately. I know the way their control yokes feel at rotation, the way their cabins smell like hot engine oil and vinyl. I know the rattle behind the panel that every mechanic hears but none can fix. In other words, the Duck is hardly imaginary. He is an affectionate amalgam of real birds I’ve taken aloft, sometimes cursed at, but always trusted. I know exactly what it feels like to coax them to life on frigid Colorado mornings, and off of short runways on a 95-degree-check-density-altitude afternoons with little headwind, while making mental bargains with the universe. But Cordell Logan isn’t me, and fiction isn’t a flight plan. Logan is a man whose life has been rough around the edges, dented at the corners, and patched together with experience he doesn’t always talk about. He belongs in a plane with similar mileage. A Cirrus wouldn’t suit him—not because he couldn’t fly it, but they both would look out of place. Logan’s a guy who needs to be flying something that simultaneously annoys him, challenges him, and reflects back the parts of himself he’d prefer to ignore. The Duck is perfect for this. It’s anything but shiny. It’s stubborn. It’s loyal. It’s loud. It holds a grudge. The Cirrus, on the other hand, suits me for precisely the opposite reasons. For one thing, it moves. If you’ve ever flown a Cherokee 180 or an old Cessna 172, you know that “cross-country” means “pack a lunch and don’t wait up for me for dinner.” A Cirrus, by contrast, makes you feel like a responsible adult who can actually get somewhere before dark. The avionics are another reason. After years behind steam gauges and radios that hummed like they were built like Marconi, stepping into the Cirrus felt like being ushered into the future. It packs the kind of avionics that leave you confident that if something does go sideways, you’ll know the score before the airplane begins making its own decisions. Also, like all Cirrus aircraft, mine comes with a parachute—a giant, entire-airplane parachute. If the engine abruptly quits and I can’t get it re-started, I pull a little red handle and we drift back to earth. Logan has no such options. And that, I suppose, is a fine thing, because it raises the life-or-death stakes inherent in any good murder mystery. Still, the biggest reason Logan flies the Duck while I fly a Cirrus is that airplanes in fiction are characters, not conveyances. The Duck complicates Logan’s life. The Cirrus simplifies mine. The Duck forces Logan to stay alert, stay humble, and occasionally improvise with the enthusiasm of a man who suspects the universe has it out for him. The Cirrus lets me get where I’m going without too much spontaneous spiritual growth. And after hundreds of hours in Cessnas and a decade in a loyal Cherokee, I can say with authority that Duck-like airplanes in particular have individual personalities, if not souls. The Duck is not a punchline. He’s Logan’s partner in crime.

Of Flukes and First Drafts: Why Whales Are a Lot Like Writing a Novel

https://davidfreed.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/whales.mp4#t=0.01 I recently went whale watching with family off the coast of Santa Barbara, where I live, and had an epiphany. It struck me after several close encounters with humpbacks—one so close its exhale misted us like an enthusiastic carwash—and only later, when a few modest Minke whales finally zipped past our boat like plus-sized dolphins on a schedule. The epiphany was this: whales are a lot like writing a novel. Both are massive, mysterious undertakings that make you feel tiny and awestruck in equal measure. Both demand patience, humility, and a tolerance for long stretches of nothing much happening—until, suddenly, something breathtaking does. There’s nothing like staring into the small, dark eye of a humpback as it surfaces beside your boat to remind you that you, the novelist, are not in charge of much. The whale decides when to appear, how long to linger, and when to vanish again into the deep. You can clap, gasp, point all you want—she’s operating on whale time. Writing a novel is like that. You spend long, hopeful hours watching an empty horizon, wondering if that first great breach of inspiration will ever come, and when it finally does, you’re so stunned you nearly drop your camera phone overboard. At first, whale watching looks deceptively simple: buy a ticket, board a boat, scan the sea. Likewise, writing a novel begins with equal naïveté: open laptop, pour coffee, write “Chapter One.” How hard could it be? Then the water stretches out before you—vast, inscrutable, blue-gray—and you realize you might be here a while. That’s when you start thinking dangerous thoughts like, “Maybe I should’ve brought snacks,” or “Maybe I should’ve written haiku instead.” And then—just when you’re sure you’ve made a terrible mistake—a humpback appears. She exhales a misty plume, and your heart does the same. The first sentence, the first chapter, the first something rises up out of nowhere, full of promise and life. It’s magnificent. It’s also gone again in seconds. The rest of the novel will now consist of waiting for that creature to resurface in some recognizable form. Only later do the Minke whales show up—your draft chapters you’d rather not talk about. They’re smaller, quicker, and, if we’re being honest, a little less dramatic than their humpback cousins. They pop up, make a modest showing, then disappear before anyone’s ready with the camera. You respect them for showing up at all, but no one gasps when they do. They’re necessary, though—the practice whales. They keep the ecosystem alive between the great breaches. Every writer has their Minke moments: the serviceable scenes, the decent dialogue, the words that simply get you to the next sighting. Without them, you’d lose heart waiting for the humpbacks to return. Whales don’t move fast. Neither do novels. Both take time—months, years, epochs—to migrate from one idea to another. They travel great distances through invisible depths, surfacing just often enough to remind you they’re still there. That’s what writing feels like on a good day: a slow, muscular progress through something larger than you can comprehend. You’re always slightly humbled by the scale of it. The ocean doesn’t care if you’re seasick, sunburned, or short on adjectives. It has its own schedule. So does your story. And then there’s the teamwork aspect. On the boat, you’re surrounded by other passengers—each convinced they’re the one who spotted the whale first. In writing, everyone’s got advice: editors, beta readers, your friend who’s “always wanted to write a book.” You nod politely while keeping your eyes on the horizon. Because deep down you know that when the next whale surfaces—when that chapter finally sings—you’ll be the only one who can say what it means. Whales are also masters of sound. They sing across oceans, communicating with voices that travel for miles through dark water. Writing, too, is an act of unseen resonance. You send your sentences into the void, hoping some distant reader will feel them vibrate. You may never meet the person who hears your song, but if you do it right, they’ll know it came from the deep. Of course, there’s always the possibility that the whales won’t show up at all. Every captain admits it’s a risk. “They were here yesterday,” someone will say, scanning the waves. “You just missed them.” Writers know that feeling too—the long, empty days when the story’s gone missing, and all you can do is keep scanning the page. But the only thing worse than not seeing whales is giving up and going back to shore. Eventually, if you’re patient, something astonishing happens. The humpback breaches, exploding out of the sea in a roar of water and sunlight. The crowd erupts. Every camera clicks. You know you’ve witnessed something beyond explanation—a creature so immense it makes you feel both small and connected, fleeting and eternal. That’s the moment you chase as a writer: when all your waiting, your false starts, your Minke-sized drafts culminate in a single, undeniable act of creation. Then it’s gone again. The ocean closes. The whale leaves you drenched, exhilarated, and slightly dazed. You review the photos and realize they don’t capture it—the grandeur, the mystery, the sheer presence. You have to go back out tomorrow and try again. Because that’s what writers—and whale watchers—do. We keep showing up for the miracle.

On Robert Redford

I once met the actor and director Robert Redford. I was a young reporter in Denver back then, covering the state legislature and Colorado governor’s office for the now-defunct Rocky Mountain News. I’d received a tip that Redford was set to have breakfast the following morning at the Governor’s Mansion with then-Gov. Dick Lamm. I showed up early and met Redford at the door. After introducing myself, I asked why the two men were meeting? He brushed me off—politely—and suggested we could talk at a function later that day where he was scheduled to speak publicly. When I approached him there, he brushed me off once more, again politely, with that characteristic mix of charm and aloofness that seemed effortless for him. I don’t remember what his purpose in Denver was that day. I do, however, vividly remember how he struck me in person. He was shorter and even more handsome than on screen. He wore a wool sportscoat, trousers, cowboy boots, a western-style shirt, a beaded Navajo belt, and aviator-style glasses with a tiny chip missing from the corner of one lens. It was such a small, humanizing detail for someone who seemed otherwise carved out of cinematic perfection. What has stayed with me more than that memory, though—call it confluence or simple coincidence–is how much of my own life seemed to weirdly intersect with some of his films. In my late teens, for example, I got big into winter mountain camping, influenced largely by Redford’s portrayal of the rugged frontier loner in Jeremiah Johnson. That illusion ended abruptly after I fell through the ice of a freezing mountain stream above Colorado’s Guanella Pass, where a blizzard set in and a buddy and I were snowbound for a couple of days, unable to hike through tall drifts back to his truck. Shivering in my sleeping bag, wet, cold, and hungry, with little more to eat than freeze-dried oatmeal, I realized quickly that I was not, and never would be, Jeremiah Johnson. I chose to become a journalist in large measure after watching All the President’s Men. Seeing Redford as Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, relentless in pursuit of the truth with his partner, Carl Bernstein, made the job look not only meaningful but thrilling. While still in college, I watched Three Days of the Condor, in which Redford plays an unwitting intelligence analyst caught in a web of espionage. Not long after graduating, the CIA recruited me and flew me back to Washington for a series of job interviews. The position they were considering me for was not one that I was particularly keen on, and the job was never offered. Many years later, after leaving daily journalism, I would wind up working under contract for both the CIA and the DIA. My work was hardly the stuff of Hollywood spy flicks, but walking around inside the intelligence community with a top-secret clearance did make me feel, perhaps if only a little, like I was inhabiting a Redford role. Redford played a barnstorming, devil-may-care pilot in The Great Waldo Pepper, flying around in an open-cockpit biplane. I, too, became a pilot, though a much more cautious one. There were other intersections, if you could call them that. I once was invited to audition for a non-speaking part in The Electric Horseman, a modern Western starring Redford and Jane Fonda. The audition required that I show up at a modeling agency one hot summer day, wearing a flannel shirt (why a flannel shirt, I have no idea). In any case, as I drove into the parking lot, I observed several studly-looking young men milling about outside. They all looked like professional actors, and they were all wearing flannel shirts. I decided in that moment that I was not an actor and had no desire to be one. I drove out of that parking lot and never looked back. Years later, as a working screenwriter, I pitched a couple of movie ideas to executives at Wildwood Productions, Redford’s film development company. Alas, my pitches went nowhere. What was no less disappointing was that I never saw Redford in his office; I still wanted to ask him about that mysterious breakfast with Gov. Lamm. This morning, news came that Robert Redford had passed away at 89. It’s hard to reconcile that he was as old as he was. He seemed timeless, the embodiment of vigor and youth. To me, he was more than a movie star. He was a mirror, however distant, reflecting back the ambitions, adventures, and even missteps of my own life. In a way, I’d like to believe that many of his films became personal guideposts, nudging me toward choices that shaped who I ultimately became. They provided me with more than entertainment. They gave me the sense that, even for a poor kid from Colorado, it was possible to lead a life with curiosity and perhaps even a touch of daring. What also made Redford noteworthy was that he never limited himself to the bright lights of Hollywood. He poured his influence, money, and energy into causes that he believed mattered—protecting the environment, preserving open spaces, elevating independent voices in film, and fostering civil discourse. He founded the Sundance Institute not only to showcase fresh talent, but to create a community where stories outside the mainstream could find life. His activism was steady and genuine, proving that celebrity can serve more than self-promotion; it can offer stewardship. Robert Redford reminded us that the world is larger than our fears, richer than our routines, and worth chasing with everything we’ve got. That is how I’ll remember him: not just as an actor, director, or benefactor, but as a man whose stories helped me find my own.

Banana-Free: Confessions of a Fruit Heretic

“Why don’t you like bananas?” This is a question I used to get constantly from my children, and get constantly from my grandchildren, all of whom are militant banana enthusiasts. These are people who will eagerly wolf down bananas straight from the peel, sliced onto their cereal, blended into smoothies, and baked into muffins. They view the banana not merely as a fruit, but as a foundational food group. I, meanwhile, view bananas as an evolutionary mistake run amok. Banana-related conversations with my grandkiddos often go something like this: “Poppy (or Papa, depending on the kid), why don’t you like bananas?” “Because I don’t.”“But why?”“Because they’re weird.”“No, they’re not.”“Yes, they are. They’re squishy and they smell funny.”“But they taste good.”“To you, maybe.”“But why don’t you like them?”“I just explained it to you.”“I know, but why?” This is what I’m up against—a gaggle of persistent little fruit loyalists demanding justifications I can’t scientifically validate. If I told them I was allergic to bananas, they might show mercy. If I told them I once had a traumatic, banana-related incident involving a chimpanzee and a tricycle (not true), maybe they’d back off. But telling them bananas make me throw up a little in my mouth is unacceptable. You’d think I’d just confessed to hating puppies and kittens. And yet, despite this unrelenting pressure, I remain firmly banana-free. With all due respect to Dr. Seuss, “I do not like them here or there. I do not like them anywhere.” You may be thinking: But bananas are delicious and packed with vitamins. How can anyone possibly dislike them? To which I say: With great consistency and moral clarity. Let’s start with their taste and texture. Bananas are the only fruit that can be described simultaneously as mushy, chalky, stringy, and gummy. That’s not a description—that’s a warning label. And the smell? If the scent of overripe bananas was bottled, it would be called Eau de Decay and sold in truck stop restrooms. Then there is the look of them. They don’t resemble any other fruit in this or any other universe. Not by a mile. Bananas are shaped like punctuation marks. They bruise like amateur boxers. You blink at them wrong and overnight, they turn from edible to an environmental clean-up site. And yet, despite all this, bananas have become the default fruit of modern civilization. They are snuck into fruit salads and thrown into children’s lunches with alarming regularity. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve gone out for breakfast and had the waitress ask me if I wanted banana slices on my oatmeal for an extra dollar or two? No, thank you. Disliking bananas includes membership in one of the most obscure clubs on the planet. Indeed, a recent Yougov.com survey found that only 5% of American adults say they dislike bananas, compared to 86% who like them, and 8% who are “neutral”, which I guess means they wouldn’t necessarily go out and buy a banana, but they wouldn’t call the cops if one showed up in their fruit bowl, either. Tragically, we who dislike bananas have no support group. No bumper stickers. No “Banana-Free Body By Choice” lapel pins. We simply suffer in silence, declining banana smoothies and discretely picking out, then flinging away, the banana slices from potluck picnic fruit salads. I figure what we need is a famous-person spokesperson—someone who shares our disdain for all things banana and can serve as the face of our movement. Unfortunately, the only celebrity I could find who comes close is Kendall Jenner, who has said publicly she doesn’t like bananas because she associates the smell with her father, Caitlyn Jenner, who ate them constantly when she was growing up. The smell, she said, gives her a headache. The problem is, I’m not sure Kendall Jenner is the kind of rallying figure who can carry the torch for banana haters everywhere—mostly because I really have no idea what she’s famous for. Which brings me back to the home front. To my grandkids: I love you, and I do not judge. If you like bananas, knock yourself out. But no, I will not eat one with you. Not a bite. Not even “Just try it, Poppy”—because we’ve been through this before. Many times. And if you ask me again why I don’t like bananas, I will look you in the eye, yet again, and say what I always say: Because I don’t. And that, dear reader, should be reason enough.

To the Moon… But Not the Mall: My Love Affair with Rockets and the Politics of T-Shirts

Anyone who knows me knows I have a soft spot for anything that flies—with the notable exceptions of mosquitoes and those terrifyingly winged monkeys from The Wizard of Oz. I was convinced as a kid that one of those flying demons was going to swoop down in broad daylight and snatch me out of the backyard. To this day, I still can’t watch that movie without feeling a bit anxious. That said, if it flies and doesn’t cackle or drink blood, I’m a fan. I’m particularly fond of fixed-wing aircraft (i.e., airplanes). I like helicopters, too, despite their apparent defiance of basic aerodynamic laws. But rockets? Rockets have always held a special place in my heart. As a kid, I built and launched many model rockets, all of them powered by what were marketed as “engines” but which were, in fact, firecrackers on steroids. Somehow, despite numerous close calls and at least one near miss involving my sister, I still own all ten of my fingers and both eyes. Like most kids growing up in the golden age of space exploration, I saw astronauts as gods, encased in their white flights suits and bubble helmets. I’m old enough to remember all of the Apollo missions, back when going to the moon was something mankind actually aspired to. As a newspaper reporter, I once was assigned to cover the landing of the Space Shuttle Columbia at White Sands Missile Base in New Mexico. Watching it touch down was like watching Zeus himself hurtling in from Olympus on a flaming chariot. These days, I get my rocket fix a little closer to home. I live not far from Vandenberg Space Force Base, where launches of SpaceX rockets lugging communications satellites into low earth orbit have become frequent enough that I’ve started to recognize the size of the rockets merely by the severity of the window-rattling sonic booms they produce. (Pro tip: the Falcon 9 sounds like God kicking a dumpster full of anvils.) Naturally, my enthusiasm for spaceflight led me to acquire a few SpaceX t-shirts on eBay. They’re comfortable, reasonably priced, and they have rockets on them. What more could I ask for? I wear them proudly—at least, I used to. This is where things get complicated. As most people know, SpaceX is owned by Elon Musk, a man who is either a visionary genius, a chaos agent, or possibly just a very rich guy with too much time on his hands. No matter how you view him, however, one thing is clear: the man definitely is polarizing. And in my household, let’s just say he’s not exactly winning any popularity contests. My wife—who is as rational and tolerant as she is politically aware–has gently but firmly informed me that wearing SpaceX merch in public is, in her opinion, “not a great look.” She hasn’t banned the shirts outright, mind you. That would imply I have no autonomy, which I do. In theory. But she has made her displeasure known through a highly effective combination of sighs and subtle-but-devastating comments like, “Are you sure you want to wear that to dinner with the neighbors?” So now, my beloved SpaceX t-shirts are mostly relegated to in-home use, joining the ranks of other rarely worn garments, including my vast collection of Denver Broncos team jerseys, and the “Parrot Head” tank top I bought years ago at a Jimmy Buffett concert. Even inside the house, wearing a SpaceX t-shirt will draw frowns of disappointment that read, “I can’t believe I married this man.” I try to explain that I’m not endorsing Elon Musk—I’m endorsing his rockets. The marvel of science. The miracle of controlled explosions. But nuance, apparently, does not fit comfortably on cotton-poly blend. I wish everything wasn’t so political these days. Can’t a guy just wear a comfy shirt with a rocket on it without having to issue a disclaimer? I’m not aligning myself with any ideology—I just like things that go “whoosh” and defy gravity. That’s it. If the rocket also happens to be designed by a weirdo billionaire with 14 children, that’s, well, unfortunate, but it’s not really the rocket’s fault. It’s hard being a rocket enthusiast in the era of outrage. I feel like I need to carry a little card in my wallet that says: “The opinions expressed by this t-shirt do not necessarily reflect those of the wearer. He just likes things that fly.” Still, I wear them. Not to make a point or start an argument—just quietly, when she’s out of town or working late. There’s no rebellion in it. There’s something about putting on a shirt with a rocket on it makes me feel a little more like my younger self—the kid who thought (and still does) that astronauts are indeed the embodiment of The Right Stuff. My wife doesn’t love the association, and I respect that. Marriage, after all, is built on a thousand tiny negotiations and arrangements. She gives me room to indulge my quirks, and I try not to wear my quirks in public. But now and then, when the coast is clear and the house is quiet, I’ll put on one of my SpaceX t-shirts, step outside, and look up—just in case something’s launching. In that moment, politics fade, and all that matters is the sky.

Book lovers, thrill-seekers, and snack enthusiasts—unite!

This Saturday, come hang out at Tecolote Book Shop (1470 E. Valley Road, Montecito) for a reading and signing of my new Cordell Logan adventure, DEEP FURY. Logan’s a former government assassin turned flight instructor.I’m the guy who keeps making his life complicated—for your reading pleasure. We’ll have books, snacks, drinks, and hopefully a few laughs.Hope you can make it—it won’t be the same without you!

Where Did “Bougie” Come From, and Why Are We All Expected to Know What It Means?—A Totally Not-Bitter Linguistic Rant

Let’s talk about bougie. Not because I want to, but because apparently, I have to. One minute I’m living my life peacefully, eating Cheez-Its from the box like a perfectly normal person, and the next, someone tells me that my snack of choice is “not very bougie.” Suddenly I’m spiraling. Do I want to be bougie? Am I supposed to be? Is Cheez-Its-from-the-box anti-bougie or post-bougie? Is there a chart? This, dear reader, is the modern linguistic dilemma: the way new slang drops into the public consciousness like a Taylor Swift album. Suddenly everybody else understands its significance, and you’re just standing there, Googling it on your phone under the table like a complete doofus because you have no idea what it means. But let’s back up a bit. The word bougie is a shortened version of bourgeois, which you may have tripped over in high school English class during a bored reading of Animal Farm. Originally, the word referred to the middle class—especially those with materialistic values. But somewhere along the way, bourgeois got rebranded, dropped a few syllables, and emerged as bougie, ready for its close-up in Instagram captions and conversations with predominately younger people. Now, bougie isn’t just a word. It’s a vibe. It’s used to describe anything fancy, overpriced, curated, artisanal, or generally engineered to look fabulous but cost at least 40% more than it should. Think charcuterie boards, pet acupuncture, or a $19 salad with edible flowers and hand-crafted croutons milled exclusively from Durum wheat. Like so many words before it, bougie didn’t arrive through official linguistic channels. There was no press release. No public service announcement from Merriam-Webster. It just showed up one day—probably in a tweet—and everyone pretended they’d known it forever. This isn’t new. Every generation has its linguistic curveballs. Think back to the first time you heard someone say woke and weren’t sure if they meant well-rested. Or when ghosting stopped being something Casper did and started referring to people vanishing like magicians with commitment issues. Or the moment super became an adjective or adverb sprinkled on literally everything. Super cute. Super annoying. Super not okay. Somewhere along the line, apparently, very wasn’t cutting it anymore. We now needed our intensifiers wearing spandex and capes. Suddenly, your neighbor wasn’t just tired—she was super tired. Your pancakes were merely good—they were super good. And let’s not even talk about the time your friend described their relationship with their ex as “super complicated,” which turned out to mean, “We broke up last year but still share custody of the cat.” It’s like someone gave the English language a Red Bull and said, “Here, drink this and go wild.” And it did. What’s especially maddening is how these words are used with such confidence—by teenagers, coworkers, and that one snarky barista at Starbucks with the septum piercing who always judges your order. Suddenly, you’re the weird one for not knowing what cheugy means. (Side note: I still have no idea. I think it means Millennial, but in a rude way.) We live in an era of accelerated language evolution. Social media these days can turn slang into a viral commodity, spreading words faster than a case of measles in Texas. One clever TikTok video and, boom, a word can go from obscure to omnipresent overnight. Before you can blink, your 85-year-old aunt is misusing it in her Facebook posts, and it’s already uncool. There is, of course, no way to keep up. You can memorize Urban Dictionary like it’s the LSAT. You can lurk silently in Gen Z group chats (though that’s definitely not cool). But eventually, some shiny new word will appear, and you’ll do what we all do: nod like you get it, then frantically Google it. Even worse, once you do figure it out and start using the word with some degree of confidence, the youths of America will inform you—often with a condescending smile—that it’s “cringe” now. (Which, by the way, used to be a verb and is now apparently a lifestyle assessment.) So where does this leave us? From my perspective, ever confused. But also kind of in awe. Because, as frustrating as this ever-shifting lexicon is, it’s also proof of how alive language can be. Words aren’t fixed in time. They evolve, morph, shed meaning, gain swagger, and show up whether you invite them or not. And yes, that means we’ll never be fully caught up. We’ll always be chasing after the latest slang term like when you were a kid and there goes the ice cream truck. But maybe that’s okay. Maybe part of being human in the 21st century is learning to live with linguistic whiplash and accepting that someday—probably soon—bougie will be replaced by something even more baffling, like plunch (my prediction for 2026: a brunch/lunch hybrid served exclusively on uncomfortable furniture). Until then, I’ll keep eating my Cheez-Its from the box and pretending I’m grounded and humble–not because I can’t afford goat cheese-stuffed, Castelvetrano olives or truffle popcorn, but because I reject elitist snack culture. Or maybe, quite possibly, I’m just not bougie enough.

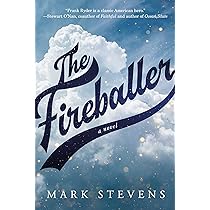

The Perfect Game

Upon occasion, you come across a novel that—if you’ll pardon the cliché—hits it out of the park. You crack open the first page, and by page two, you know you’re in trouble. The kind of trouble that keeps you up past midnight, ignoring text messages, blowing off obligations, and contemplating how much sleep you really need before work the next morning. The story grabs you by the (insert your favorite anatomical reference here) and refuses to let go. The Fireballer, written by former journalist and veteran novelist Mark Stevens, is one such novel. Set against the backdrop of Major League Baseball, the book immediately transported me back to a world I once held dear. As a kid, I followed the game religiously. But as an adult, I drifted away—disillusioned by the rise of free agency in the early 1980s, when it seemed that players hopped from team to team like free radicals. What used to feel like a lifelong bond between athlete and city began to resemble a rotating-door business contract. Keeping up with who played for whom became a full-time job in itself. Throw in the designated hitter rule—don’t get me started!—and I all but checked out of the game entirely. But The Fireballer might just woo me back. The story follows Frank Ryder, a once-in-a-generation pitching phenom out of Denver’s Thomas Jefferson High School who signs with the Baltimore Orioles. Frank possesses an almost mythic gift: a 110-mile-an-hour fastball that is, quite literally, unhittable. His ability on the mound is both awe-inspiring and dangerous, threatening to upend the sport’s fragile equilibrium. But while the novel might sound like a classic sports underdog story on the surface, calling it “a baseball book” hardly does it justice. At its heart, The Fireballer is a powerful character study. It’s about what it means to be human in a system that often demands setting your humanity aside. Frank is not just a pitcher—he’s a thoughtful, wounded, deeply principled young man navigating a game, and a life, where morality and ambition don’t always align. I cannot remember the last time I felt such admiration and such ache for a fictional character. Frank Ryder isn’t just well-drawn; he’s unforgettable. Mark Stevens is a masterful writer. His prose is elegant without being showy, innovative without being overwrought. There’s a rhythm to his writing that mirrors the tempo of the game itself—deliberate, precise, unhurried but filled with tension. I found myself reading slowly on purpose, lingering over certain passages, re-reading others, not wanting the book to end. His world-building is airtight, his research unobtrusively embedded in the fabric of the narrative. As any writer knows, credibility matters. Get one small detail wrong, and the illusion can break. But Stevens is in full command of his material. He pulls off the literary equivalent of a perfect game. The Fireballer is an astonishing achievement. It would make a great movie. Whether or not you love baseball, I promise, you’ll love this book.